The United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel signed an historic peace agreement in August 2020. As the first Arab country in a long time to do so, the UAE has set an example, which was quickly followed by three other countries – Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan – and may also help win over Saudi Arabia in due time. The so-called Abraham Accords were brokered by the United States and entail a normalisation of diplomatic and economic relations.

Although the boycott by the Arab world of Israel since its founding in 1948 has become less strictly enforced over the years, it still provided significant impediments for travel, business and trade. The UAE’s abolishment of the Israel Boycott Law will pave the way for broad-based economic cooperation.

From covert to overt

During the many decades of the boycott, some trade and business dealings took place between the UAE and Israel. Those covert transactions were typically conducted via middlemen in third countries. The direction of trade appears to have been mostly one-way – from Israel to the UAE – and the type of merchandise limited to high-end items such as technology and diamonds.

Since the peace treaty, the authorities in the UAE and Israel have shown eagerness to bring existing trade out in the open and unlock new mutual trade opportunities. Cooperation agreements have been signed between the export credit agencies of the UAE and Israel and also between the chambers of commerce of both countries. Other steps towards more cooperation are the opening of embassies, an Israeli one in Abu Dhabi and a UAE equivalent in Tel Aviv, and the start of regular commercial flights between the two countries. According to various sources, including officials from both countries, annual bilateral trade could be ranging anywhere between USD 4.0 – 6.5 billion in the medium term, which is equivalent to about 1.0%-1.5% of each country’s GDP. A big improvement from the near zero trade recorded in the official bilateral trade data.

A good match at first sight

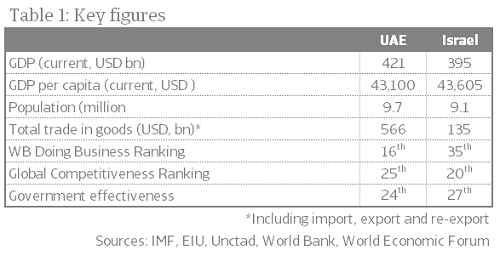

In terms of economic size and level of development, the UAE and Israel are much alike. They both have a gross domestic product (GDP) of around USD 400 billion and their relatively small populations enjoy a high living standard measured in per capita income (Table 1). Furthermore, Israel and the UAE are open economies. The import and export ratios of Israel are close to 30% of GDP. For the UAE those ratios are even higher, because of its large re-export volumes. The UAE is a major regional trading hub and the re-export of a wide range of goods accounts for almost 50% of its total merchandise export.

The economic growth outlook for Israel and the UAE is relatively strong, with recessions of respectively -2.2% and -7.7% in 2020 behind them. Although the global pandemic will continue to form a drag on private consumption and external demand in the near term, Israel and the UAE are the two leading examples of fast coronavirus vaccination rollout. The recent recovery in the global oil price and the easing of oil production cuts imposed by OPEC+ will gradually lift the UAE’s oil economy out of its multi-year woes. Non-oil economic activity is already expected to rebound by 3.5% this year and will continue to be supported by reforms to attract foreign investment and talent. The World Expo in Dubai in late 2021 and early 2022 can help revive the important tourism sector, though much depends on the global coronavirus vaccination rollout. The Israeli economy entered the crisis from a position of strength and will pick up where it left off with real GDP growth rates of 3.5% or higher. The fast virus vaccination rollout will allow the economy to reopen relatively quickly. Israel will benefit from offshore gas sector developments in the medium term. Sovereign risk remains limited. Although public debt in both countries has peaked above 70% of GDP during the corona crisis, large financial assets and easy access to the international capital market ensure that the financial positions of the Israeli and UAE governments remain comfortable with sovereign risk rated as A+ to AA- respectively.

Both economies are well-diversified, which will not only help the economic recovery, but also means that they potentially have a lot to offer each other in terms of product choice. While the impact of the global pandemic is heaviest and most protracted on service-based sectors, high-tech manufacturing has proven more resilient and global trade in manufactures in general staged a recovery. Although the UAE is a traditional hydrocarbon producer, it is one of the most diversified economies in the Gulf region. In fact, more than 70% of UAE’s GDP comes from non-oil resources. Israel’s merchandise exports cover a broad spectrum of chemicals and manufactures. Moreover, the favourable business environment in the UAE and Israel bodes well for developing an intimate trade relationship. This is reflected by the UAE’s 16th position in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business ranking and Israel’s 20th place in the Global Competitiveness ranking. The support from high quality institutions and good access to finance will further facilitate trade.

So with the boycott lifted, there shouldn’t be too many obstacles in the way that could hamper bilateral trade. To really boost trade, the countries agreed to look into reducing import tariffs and non-tariff measures in strategic sectors. A more fully-fledged free trade agreement may be negotiated in the medium term.

Mutual trade opportunities

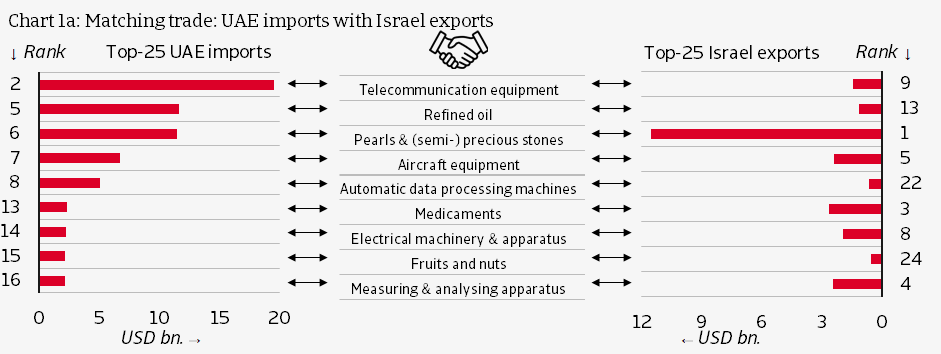

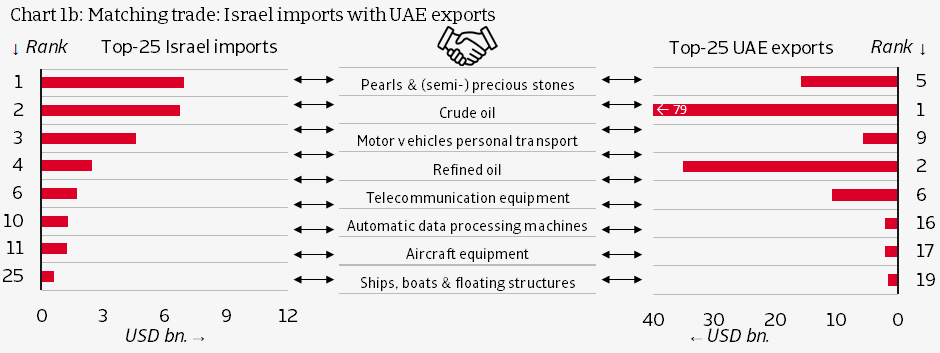

A crude way to identify mutual trade opportunities is to check for which main product categories the import and export flows of the UAE and Israel complement each other. When a product is in the top export list of the exporting country and in the top import list of the potential trade partner, the potential trade base in terms of value is large (Chart 1a and 1b).

Of some of the most traded non-oil product categories – like telecommunication equipment, automatic data processing machines, aircraft & associated equipment and precious stones – the UAE and Israel both import as well as export large volumes. Although this means they are also potential competitors in these areas, there will still be plenty of opportunities for mutual trade, either to match product demand and supply within specific segments of those broad product categories or for re-export purposes in case of the UAE.

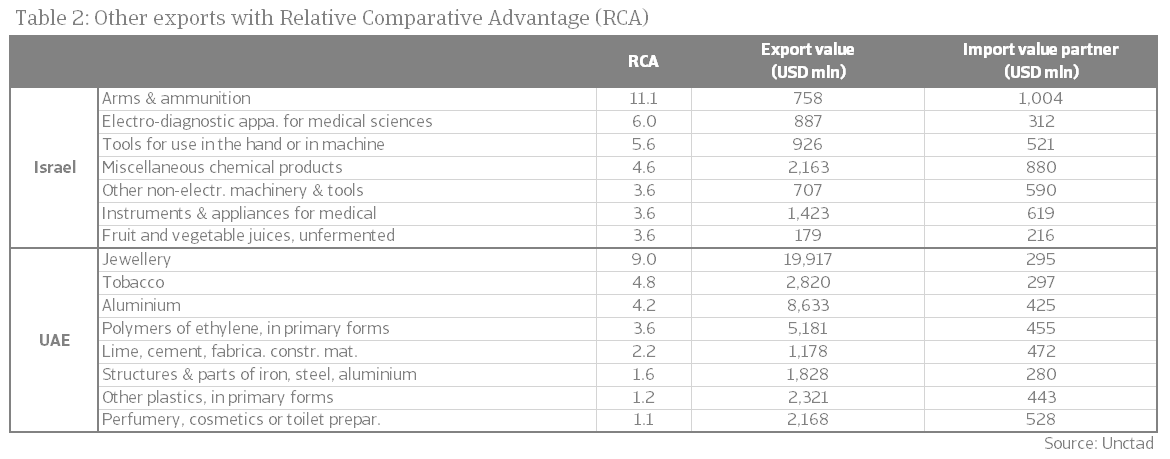

For other product categories, the UAE and Israel are more natural trade partners. The UAE is for instance a heavy importer of medicaments, electrical machinery & apparatus, fruits & nuts and measuring, analysing & controlling apparatus, which are all items that rank high in Israel’s assortment of export products. Israel, on the other hand, has a strong demand for motor vehicles and ships that the UAE could possibly satisfy given that those products fall within the UAE’s top (re-) export categories. It should be noted, however, that Israel’s current trade partners may be better positioned than the UAE to provide motor vehicles and ships, as the UAE does not have a comparative advantage in those products. The revealed comparative advantage (RCA) compares the country’s export share of a product to the share of the same product in global exports. A RCA greater (smaller) than 1 indicates a comparative advantage (disadvantage) over other countries for a particular product category. Exports products for which the UAE has an RCA greater than 1 are perfumery, plastics, aluminium and cement & other construction materials (Table 2). The UAE clearly has an edge in infrastructural development. The construction materials category includes ceramics of which the UAE is a top world exporter. Israel has a strong comparative advantage in arms & ammunition, medical electro-diagnostic devices, chemical products and unfermented fruit and vegetable juices.

UAE could trade-up in technology

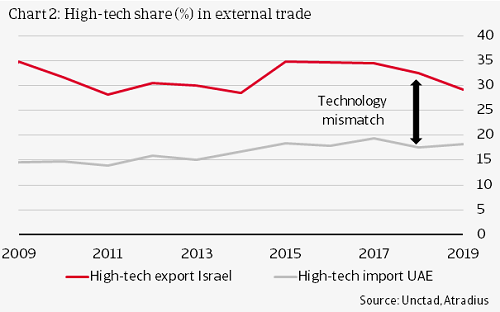

A distinctive factor in the current trade pattern is the high-tech content. Israel is well-known as one of the world’s high-tech producers. It is not without reason that leading technology firms like Intel have a large manufacturing base in the country. Around one-third of Israel’s total exports can be labelled high-tech and this share goes up to almost a half when resource-based exports are excluded. The technology mismatch with the UAE does not have to be a problem, but can be another opportunity for cooperation instead. While the UAE sells mainly low/ medium-tech and resource-based manufactures it is gradually trading-up, buying more high-tech items from around the world. The UAE’s share of high-tech import products has increased from below 15% to almost 20% over the past 10 years (Chart 2). This pioneering in technology products coincides with the UAE’s accelerating economic diversification drive. FinTech start-ups are for example welcomed in UAE’s free zones and the UAE is having success with its space program. The technologically advanced Israeli companies are strong in those fields and through either trade or investment the UAE could benefit from Israeli expertise in healthcare and agri-technology as well. The UAE is making a significant effort to attract foreign investors and is already one of the largest recipients of FDI in the Gulf region. The Dubai World Expo later this year, where Israel will have its own pavilion, is a great opportunity for Israeli companies to showcase their innovations.

Dutch disease threatens Israeli competitiveness

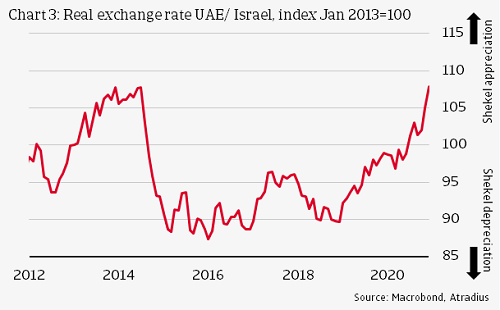

A concern is that Israeli export goods could at some point become too expensive for the UAE. Israel’s gas production expansion since the Tamar field became operational in 2013 would be the culprit. Higher gas revenues are making the Israeli shekel stronger, eroding Israel’s international competitiveness position in other important export sectors like manufacturing. This phenomenon is known as "the Dutch disease", named after the Netherlands, which suffered a similar loss of competitiveness after a discovery of a major gas field in the late 1950s.

Export from Israel’s newly developed large Leviathan offshore gas field started in 2020 and will scale up with the conclusion of new mega gas deals such as recently with Egypt. Israel’s real effective exchange rate has already appreciated by almost 8% since 2016. Without the structural intervention of Israel's central bank in the foreign exchange market, the shekel appreciation would have been much greater. However, the central bank’s neutralising policy could not prevent the much sharper appreciation of Israel’s bilateral real exchange rate with the UAE (Chart 3). Israeli goods became 20% more expensive in terms of UAE goods over the same period. The depreciation of the dirham on the back of a weakening US dollar (to which it is pegged) and the deflation of UAE consumer prices because of the global oil price dip are responsible for the extra divergence in bilateral competitiveness.

Export from Israel’s newly developed large Leviathan offshore gas field started in 2020 and will scale up with the conclusion of new mega gas deals such as recently with Egypt. Israel’s real effective exchange rate has already appreciated by almost 8% since 2016. Without the structural intervention of Israel's central bank in the foreign exchange market, the shekel appreciation would have been much greater. However, the central bank’s neutralising policy could not prevent the much sharper appreciation of Israel’s bilateral real exchange rate with the UAE (Chart 3). Israeli goods became 20% more expensive in terms of UAE goods over the same period. The depreciation of the dirham on the back of a weakening US dollar (to which it is pegged) and the deflation of UAE consumer prices because of the global oil price dip are responsible for the extra divergence in bilateral competitiveness.

For some products Israel’s export prices already seem to be at the high-end compared to the prices that are charged by UAE’s current trade partners. This is for example the case for various optical instruments and X-ray apparatus, which are specific products that are highlighted as trade opportunities in a joint study by the chambers of commerce of Dubai and Israel (Chart 4).

Although the technologically-advanced Israeli companies may simply offer more value for money than competitors, it is an indication that they do not have a lot of room for manoeuver in terms of cost competitiveness. The shekel will continue to strengthen gradually, which at some point could price Israeli companies out of the UAE’s market.

Could trade relations break down again?

Another risk is that the new relationship between the UAE and Israel will not last. This risk seems to be low for now, but shouldn’t be entirely discounted. The historic friction between the people of Israel and the Emiratis takes time to resolve. Moreover, the interest that the governments of both countries have in their relationship is not perfectly aligned. A main motivation for Israel’s engagement is expansion of trade and investment. With access to UAE’s regional trade hub Israel gains an essential foothold in the Middle East and North-Africa market. While to some extent the UAE would be able to use Israel as a gateway to the Mediterranean and the rest of Europe, this is less crucial. Security cooperation with the UAE provides Israel with a regional military ally should tensions with Iran escalate. Israel has its own strong military capabilities and a longstanding strategic alliance with the US, but it has always remained more or less militarily isolated in the geopolitically instable Arab world. Aside from the possibility to trade-up in technology, the UAE benefits from political leverage it gains from the peace treaty with Israel. It has created goodwill with the United States that has brokered the deal and opened the door to the strategically important USD 23 billion purchase of F-35 advanced fighter jets from the US, which Israel no longer opposes.

In view of the above, the UAE would be the one most likely to renege on some of the new cooperation agreements with Israel in case geopolitical tensions rise. It has less to lose by doing so, especially if it turns out that the F-35 deal that is currently being re-examined by the new Biden-administration is not approved eventually. A scenario in which the UAE could decide to reinstate a partial or full boycott would be Israel’s annexation of the West Bank, a plan that is now put on hold as a pre-condition to the Abraham accords. In Israel’s fractured political landscape, with frequent elections and a strong nationalist voter base, the annexation plan may at some point be put back on the agenda. If Israel-Palestine tensions escalate, the UAE may succumb to regional pressure to reimpose a boycott. While other Gulf States are warming to rapprochement with Israel, the UAE has also received criticism from the Middle East – especially from the Palestinians – for normalising relations before negotiating a two-state solution between Israel and Palestine.

In the first five months since the historic peace treaty, around USD 1 billion in mutual trade has been conducted. This is a promising start and indeed some of the markets that we have identified above are the initial focal points of trade. Despite the risk of a temporary setback in times of rising regional geopolitical tensions, the cooperation between the UAE and Israel that is currently being developed appears to be deep and broad-based, and will therefore not be easily undone. Reconciliation with Israel is being followed by other Arab countries, making individual backtracking more difficult. The shared interest of maintaining a strategic partnership with the US is another political safeguard. From an economic perspective, opportunities for trade and technology exchange seem too good to pass up easily.

Niels de Hoog, economist

niels.hoog@atradius.com

+31 20 553 2407

All content on this page is subject to our Disclaimer, available here.

- The recent normalisation of diplomatic and trade relations between Israel and the UAE will unlock mutual trade opportunities. Both are open and diversified economies with a favourable business climate and a robust medium-term economic outlook.

- UAE companies can satisfy Israeli demand for aluminium, ceramics and other construction materials, while Israeli companies can help the UAE advance in the high-tech field. The gas revenue driven strengthening of the Israeli currency is a potential competitiveness issue.

- Despite potential regional geopolitical tensions, with the possibility of a temporary reinstatement of the boycott, we expect the cooperation between the UAE and Israel to be intensified in the long term.